Naming the Land

As members of CPT we believe it is important that we ask ourselves questions about the land and our relationship with it. How does the land provide for us and what are our responsibilities to it? Are we visitors? settlers? exiles? Is our land under occupation or are we occupying someone else’s land? Is the land threatened or being damaged? Whose land is it and what struggles might they be involved in to return or to remain on their lands? The following writings were submitted by CPT corps members and interns from different locations and project sites as meditations on the land. As you read them we invite you to think in a new way about the place where you live and the land that sustains you.

- Kurdistan, Iraq: Dangerous Forest

- U.S.A.: Chicago – Under the Asphalt

- Palestine: To Our Land

- Colombia: Ancestry vs. Legal Title

- Borderlands: Embers of Resistance

- Canada: a Sickness Passed on to the Children

- Earth, the Mother

Kurdistan, Iraq: Dangerous Forest

by Chichun Yuan

This is a fertile land. In spring, different colors of flowers pop up every week for bees. In summer, the sunflower fields along the road greet the farmers harvesting the wheat. In fall, apples and citrus fruits bend the tree branches so you can pick them easily.

But in some places thousands of unexploded devices lie in or on the ground. People say the wild and dangerous forest was formed as a refuge for wildlife after the war stopped, but human beings are forbidden to enter.

The militaries from different countries continue to plant landmines to hurt themselves and the other people. One landmine brings three dollars to the company that sells it. But to clear one costs the international community 300-1,000 dollars. According to the United Nations, whenever we clear 100,000 landmines, two million new landmines are being planted.

“Human being has transformed into a mysterious animal,” observes the mother land.

U.S.A.: Chicago – Under the Asphalt

by Claire Evans

Author’s note: In the process of researching and writing the following piece, I more than once thought that my role as a white settler should be asking questions rather than presuming to speak with authority on the topic. How differently would the Miamis and Potawatomis describe the movement of their own people? Have there been any efforts by First Nations people to reclaim land in Chicago? Could I just not find any evidence of it because of the limitations of internet searching? It is not even clear to me whether the Miamis or the French explorers decided to name the area for the wild onion! It is in the spirit of questioning, rather than providing answers, that I submit this small attempt to raise my own and other’s consciousness of the land on which we live.

Looking on the concrete and asphalt paving Chicago today, it is hard to imagine when sand dunes and prairie dominated the landscape. Or that wild onions would be a feature to give name to the place – “Chicago” being the way 17th century French explorers rendered the Miami term for that pungent and flavorful herb.

In 1803, when U.S. expansionist policies established Fort Dearborn (at the site of today’s downtown Chicago), the Miamis had already moved eastward and the Potawatomis were the predominant First Nations group in the area. In

1833, all the First Nations people remaining in the region were expelled. Indigenous people didn’t return in any numbers until the 1950’s, when the U.S. government’s Relocation Program encouraged migration to cities in a concerted effort to break the reservation system. Today, the Chicago metropolitan area is home to some 40,000 people of various First Nations, most with ancestral roots outside of the Chicago region, including Central and South America.

In the absence of any apparent effort by First Nations people to reclaim land in Chicago, those of us who live and work here would do well to:

- acknowledge the injustice that forced the earlier residents of this place to abandon it;

- respect the presence of their descendants among us;

- be mindful of indigenous land issues in neighboring states where many First Nations residents of Chicago continue to have ties.

Palestine: To Our Land

by Mahmoud Darwish

and it is the one near the word of god,

a ceiling of clouds

To our land,

and it is the one far from the adjectives of nouns,

the map of absence

To our land,

and it is the one tiny as a sesame seed,

a heavenly horizon … and a hidden chasm

To our land,

and it is the one poor as a grouse’s wings,

holy books … and an identity wound

To our land,

and it is the one surrounded with torn hills,

the ambush of a new past

To our land,

and it is a prize of war,

the freedom to die from longing and burning and our land,

in its bloodied night,

is a jewel that glimmers for the far upon the far

and illuminates what’s outside it …

As for us, inside,

we suffocate more!

Translated by Fady Joudah(From The Butterfly’s Burden, 2007, Copper Canyon. Used with permission.) Mahmoud Darwish (1942-2008) was among Palestine’s most prominent poets.

Colombia: Ancestry vs. Legal Title

Once upon a time, a campesino community lived and farmed near the village of Buenos Aires in El Peñon, Bolívar, Colombia. These men and women, along with their families, occupied and worked the former estate of Las Pavas beginning in 1995. This land belonged to their indigenous ancestors for hundreds of years, long before Europeans started issuing land titles. In 2009, the Colombian government, like the Spanish colonizers before them, drove off the people with historic connections to the land. The riches that the current people in power seek come from a palm oil mono-crop used in beauty products for multinationals such as The Body Shop. In these lands of Las Pavas lie the ancestral spirits of the campesinos’ lost community. According to anthropologists, the indigenous Malibués inhabited these lands for some four thousand years. They mixed with enslaved Africans and Spanish colonizers, forming a tri-ethnic race–Indigenous, Black, and European–whose descendants are today’s campesinos of the area. The community has venerated and guarded the cemetery and their indigenous ancestral lands, but now bulldozers, chainsaws, and oil palm have destroyed them. And the fate of Las Pavas lies in the hands of those who twist the truth and the law at the expense of these people’s livelihoods. God made the earth and its bounty for human beings to provide for their families. Inspired by their Indigenous and African histories, the men, women, children and elders of Las Pavas pray that the Spirit will move in these times to restore the community’s power to re-take possession of the land protected by their ancestors. They pray that the intentions of the powerful might be transformed so that the multinationals will leave them in peace. May we join our prayers and our actions with theirs so that it may be so.

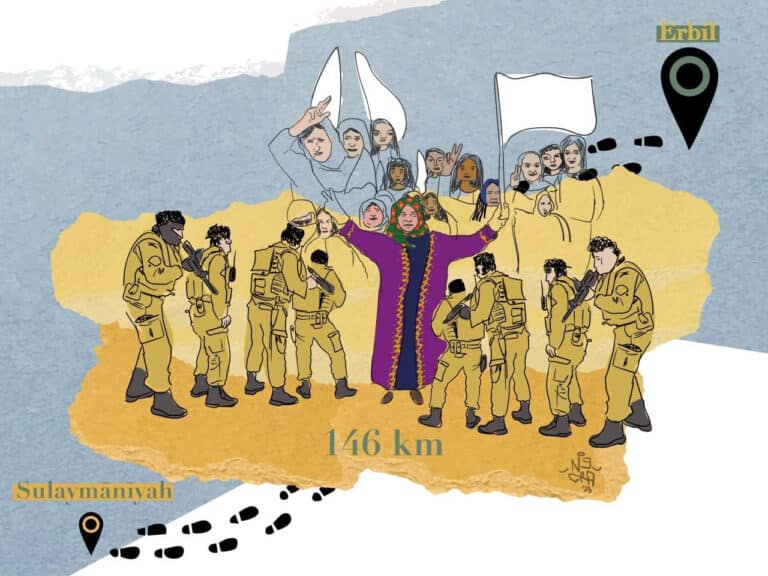

Borderlands: Embers of Resistance

We remember “The lost land” and “The Forgotten People.”

We remember the land known as Aztlan–El Nuevo Mexico–the borderlands of the present occupied territory of the southwestern United States–lands which included all of the present-day states of New México, California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona , Colorado, West Texas, and western Wyoming.

We remember the first inhabitants: the Clovis culture, the Mogollon, the Anasazi, the Pueblo, Navajo, Apache and Ute.

We remember a time without borders–when people migrated freely from the north to the south and the south to the north.

We remember the first European contact of 1492 and the European entrada of 1540.

We remember the colonial violence unleashed upon the indigenous people.

We remember the mestizo people who are the descendants of the clash of these civilizations and the result of the sexual violence wrought against the indigenous women of the “new world.”We remember that Mexicans can never be alien to the southwest because they are native people. They are part of a civilization that never went away.

We remember the trespass upon the land and the violence that ensues when one nation invades another.

We remember the killing of the bison, and destruction of the land through the uninterrupted exploitation of the natural resources by the US government.

We remember that racism is not dead.

We remember the racist manmade laws that segregate and discriminate: like the legislation in Arizona that may be technically legal but unjust-and used to divide humanity.

We remember that many immigrants are returning as a people to a place that was once theirs

We remember that militarization and failed economic policies cause migration of peoplesWe remember and rekindle the embers of resistance.

Canada: a Sickness Passed on to the Children

by Christine Klassen

When I visited Grassy Narrows I was pregnant. I asked myself, if someone offers me fish will I eat it? Fish is a staple food for the people of Asubpeeschoseewa-gong Netum Anishinaabek (Grassy Narrows). But since the 70s when a mill dumped mercury in the river, it’s not safe to eat.

Judy Da Silva said, “The mills take from our forest, and then give us back disease and sickness and death. Our people have suffered for 40 years from mercury poisoning, and now this sickness is being passed on to our children in the womb.”

Sherry Fobister, a young mother, didn’t have the choice I had: “When I was pregnant I couldn’t afford to buy food at the store, so I ate what my grandfather brought home–mostly fish. Now both my children are sick with strange illnesses, just like their cousins. I myself have tremors and numbness, but I don’t qualify for compensation. Sometimes I can’t afford to bring my kids to Winnipeg for treatment. I want everyone in Grassy Narrows tested.”

Chrissy Swain said, “It is a fight for us every single day that we wake up and have to look at our children and think about them. The land is part of who we are. We should be able to go out and hunt and fish…If all that is gone, then who are we?”

How can I even begin to understand that as a newcomer? Who am I in relationship to this land and to the nations who lived here long before my ancestors settled here? I grew up on a farm in the territory opened to settlers by Treaty Six. That’s the place I call home even though I’ve lived in Toronto for a couple of years. Four generations of my family have prospered from that land and its resources. But while we have been content to benefit from the land we have not defended it. In fact my family has been employed in the lumber and oil and gas industries that have done a lot of damage.

There’s a Bible story about Solomon and two women fighting over a child. He discovers the true mother by offering to cut the infant in two and give each mother half. The real mother immediately defends the whole child. The false mother is willing to settle for half. I see a parallel in non-Natives scrambling to own a piece of land without too much concern for how the whole planet suffers because of our activities on it. We steal from our children and grandchildren.

In contrast Stan McKay writes: “Because we understand that life is a gift, it makes no sense within our native spiritual vision for either us or others to claim ownership of any part of the creation.” (Nation to Nation: Aboriginal Sovereignty and the Future of Canada, p. 29) But the greed of non-Native settlers has forced many impoverished Aboriginal communities into a land-claim process which McKay describes as “devastating to our cultural values… The legal jargon we must use contains concepts of ownership that directly contradict our spiritual understanding of life.”

Often it is Aboriginal mothers who stand up to defend the land and are unwilling to compromise their values–women like Judy Da Silva and Chrissy Swain.

In February, 2010 I had a healthy baby girl. I took her with me on a walk organized to increase awareness about mercury poisoning and its continuing effects on the communities of White Dog and Grassy Narrows. At the rally in Queen’s Park I remembered the fish I was afraid to eat as I listened to the women and men who were willing to stand up for the future of their children and mine.

Earth, the Mother

by Malidoma Patrice Somé

Earth symbolizes the mother on whose lap everyone finds a home, nourishment, support, comfort, and empowerment. Representing the principle of inclusion, earth is the ground upon which we identify ourselves and others. It is what gives us identity and a sense of belonging…Earth loves to give and gives love abundantly. In other words, earth cares as much for the crooked as it does for the honest. Both of them are allowed to walk on her…(p. 173)

Earth is where we belong. She is our home. She gives us sustenance unconditionally and makes it possible for us to feel connected. Earth is where we go to and where we depart from. This means that she sees us in a way no one can. The nourishment and support of Earth Mother grant us the feeling of belonging that allows us to expand and grow because we feel strong. Our well-being depends on this feeling of belonging, and perhaps this is why each of us fosters some type of territorial instinct, wishing to protect that which nourishes us. Earth’s protection reflects her undivided commitment to us. We, in turn, protect her because she defines us and provides us with an abundance of resources. (p. 231)

(Excerpts from: The Healing Wisdom of AFRICA: Finding Life Purpose Through Nature, Ritual, and Community Jeremy P. Tarcher/ Putnam, 1999)