CPTnet

29 September 2015

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES SOLIDARITY: Blinded

by colonization

by Allan Reeve

[This piece has

been adapted for CPTnet. The complete reflection is available

here.]

|

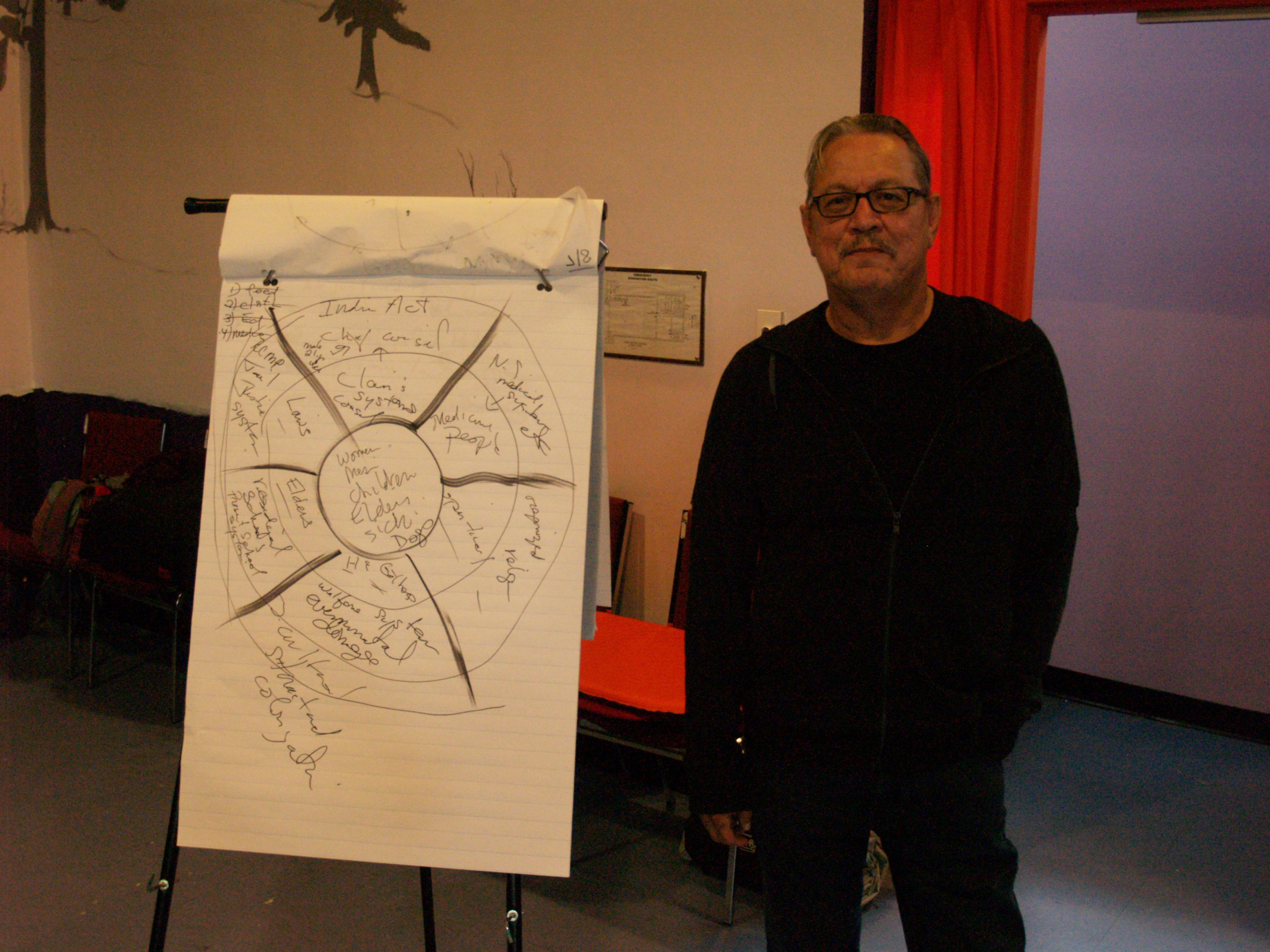

| Larry Morrisette |

“I am not sick. I

am not a victim. I have been colonized. I am a member of a strong and resilient

people. The effects of being colonized have made me sick. I have been victimized

but that is not who I am. I have been healed, and continue to heal, by the

traditional ways and medicines of my ancestors—given to them by the Great

Spirit.” (A paraphrase)

Larry Morrissette of Winnipeg’s Bear Clan (one clan among

many) explains how colonization has attempted to destroy his culture and

eradicate his people’s claims on the land we call Canada.

Larry is the

founder and president of Medicine Fire Lodge Inc., an Indigenous organization

involved in cultural revitalization through education and training. He teaches

at the University of Winnipeg. One day, he tells us, he showed up to give a

lecture and a security guard stopped him and asked him if he was looking for

the Food Bank.

He says this kind

of thing can trigger memories of abuse suffered in the residential school by

“mean” nuns. His hope is that the young people—including his children and

grandchildren—who learn the traditional teachings and use the medicines of

their people will be better able to protect themselves from such attacks on

their personhood.

“They thought we’d

be gone by now—but we’re still here.”

Larry generously shares the four directions teachings of his

Bear Clan with us. Each clan, he explains, has it’s own variations of the four

directions teachings. We’re a small group of international witnesses visiting

the Grassy Narrows blockade of the clear cutting Whiskey Jack forest. CPT has been accompanying this blockade

since it began in 2002.

That’s when young

members of the band decided to put at risk any potential benefits of

cooperating with the Federal and Ontario government. The Band Council had no

success in effecting change working through the official channels of engaging

the Federal and Provincial governments. The young people took direct action.

Larry gives us a

Canadian history lesson outlining how official policies have served corporate

interests in first conquering, then starving, then taking the Indian out of the

Indian, then assimilating, and now treating the Indian problem as a sickness—as

something to be cured through pharmacology and sociology. From the start,

European settlers’ economies led to hardship for indigenous peoples. (Clearing

the plains of bison, overhunting the forests, clustering the people on

reserves, and later on, clear-cutting the forest and poisoning the land.)

“The only reason

first nations people were given the vote in 1969 was that Lester Pearson was

pursuing status with the United Nations.”

What makes

colonization complex—and de-colonization so difficult—is a series of trade-offs

that benefits some—while discriminating against any who might stand in the way

of corporate interests. The first treaties were a trade-off. Band leaders

sought a way to feed their starving people. Then, parents looked for ways to

educate their children to equip them for colonial life. Leaders and parents

today want what’s best for their children. Because it works for some—it means

there is no unity among the people.

An example of this

“divide and conquer” strategy that works at all levels is how a few teachers

managed to control hundreds of students in residential schools. Larry explains

that the nuns would “employ” select students to serve as taskmasters, snitches,

enforcers. By adopting the tactics and serving the interests of those in power—life

was easier for them.

The question, says

Larry, is “what privileges are you prepared to risk and lose in order to be a

part of the de-colonized solution?”

“You can’t make

deals with Judy.” He’s referring to Judy DaSilva one of the blockade leaders.

“She won’t trade her rights for the privileges offered.”

Undoing

colonialism is about a communal worldview. While colonialism serves the rights

and interests of individuals—breeding consumerism in its wake, indigenous

traditions are all about taking care of the community. In a communal culture

every individual understands their identity and role in the context of the

community’s health.

For me, as a

Christian who desires to follow Jesus, the choice of communal versus individual

benefits is at the crux of the question.

The rich young man

asks Jesus what he must do. Jesus tells him to give away all his possessions.

The young man goes away sad because he has many attachments.

But is that the

end of the story? What seed did Jesus’ instruction plant in that young man’s

life? Did that young man begin to dig deeper into his indigenous heritage? Did

he begin to understand the connections between his personal privileges and the

poverty of his people?

Larry works with

gang members in Winnipeg’s North End. And he works with over-educated white

boys like me. He asks, “What privileges are you willing to risk and lose in

order to be part of the solution?”

I am sad—for I

have many attachments. I am sad—for those attachments are intrinsically part of

a globalized systemic corporatization of the resources I call Mother Earth. I

am sad—for I am no longer a young man and for all my years of working and

protesting and educating others about how to change this system—the planet, the

forests, the creatures, the peoples of the land suffer more and more.

Larry asks, “What

privileges are you prepared to risk and lose in order to be a part of the

solution?”

The Roman soldier

standing with spear in hand beside a row of crosses asks the same question.

My bank manager

looking at my mortgage application asks the same question.

My grandchildren

unable to eat the fish from polluted rivers and lakes ask the same question.

I am no longer

blind. I can see. This is the bad news about the good news of the full life

offered in the kin-dom of all my relations.

Christian Peacemaker Team Delegations lead to REVELATIONS! Apply Now!