I was fortunate to be in Chicago during CPT’s early years and to revel in friendships with some of the founding members. I remember a surprise visit from Gene Stoltzfus in 1994. “Kathy Kelly, the Lord is calling you to go to Haiti!” I laughed and asked him when. “Tomorrow,” Gene said. At the time, the U.S. was ratcheting up economic sanctions against Haiti, and within a few days international bank transactions would be prohibited. CPT needed someone to hop a flight, carrying funds to its team there, before borders crossings were also prohibited.

I spent close to three months living with the team in Jeremie, a southern province of Haiti, in an area where Ton Ton Macoute militants routinely attacked people. Eventually, we learned that local Ton Ton Macoute were anxious about our team’s weekly reports via ham radio to CPTers in the U.S. Apparently, these reports caused declining attacks amid rumors that if the U.S. military were to invade Haiti, Ton Ton Macoutes could be targeted. The local military commander, Rigeau Jean, said he was “ashamed and embarrassed that it was left to those “blans” (foreigners) on the hill to preserve the peace and security of this region.”

Yet CPT could do nothing to ease the terrible poverty afflicting neighbors in Saint Elen. I left Haiti with a lifelong remembrance of a young boy doubled over in hunger, moaning, in Creole, “I’m hungry. I’m hungry.”

CPT members again encountered lethal consequences of economic warfare through participation in delegations to Iraq where economic sanctions, first imposed in August of 1990, directly contributed to the deaths of over 500,000 children. CPT and Voices in the Wilderness (VitW) collaborated in defying the U.S./UK led economic sanctions by delivering medicines and medical supplies to families and hospitals in cities throughout the country.

After a decade long economic siege, infrastructure had deteriorated. Maintaining machines and equipment or even getting decent tires for vehicles was nearly impossible. In January of 2002, a CPT delegation traveled in a convoy from Basra to Baghdad. The drivers had safely delivered over seventy delegations to various locales, but in the scorching heat of southern Iraq, roads became dangerous because the hot pavement affected vehicle tires. One of the SUVs carrying CPT members turned over when a tire exploded, killing a Canadian team member, George Weber, and hospitalizing one of the U.S. members, Charlie Jackson. The drivers were briefly jailed and one of them faced serious legal charges. I remember learning about the tragedy from Gene Stoltzfus who called me in NYC, where I was planning, in several days, to depart for Iraq. I boarded my flight carrying a letter from George Weber’s widow, whom CPT leaders had respectfully asked to exonerate the drivers from blame. The letter, crucial for the remorse filled drivers, exemplified CPTs attentiveness to caring personal relationships even in the midst of tragedy.

Returning to Iraq, I rejoined CPT and VitW to live alongside Iraqis as the entire country awaited what seemed an inevitable U.S. led bombing and invasion. In Chicago, the CPT and VitW offices worked hard to form and prepare delegations heading to Iraq while activists in Baghdad earnestly sought visas for prospective travelers.

Dozens of team members were in Baghdad throughout the March 2003 “Operation Shock and Awe.” Day and night, we heard sickening thuds, gut-wrenching explosions and ear-splitting blasts. Lacking phones and electricity, we lost touch with everyone we knew, and communication between our team members, occupying several different hotels, became difficult. We finally managed to set up a meeting with a grim reality topping the agenda. The danger and expense of road travel out of the country was increasing each day. What would we do if medical evacuations were needed? Unfortunately, the delegation staying at the Al Dar Hotel, while walking to the planned meeting, was detained by Iraqi authorities for photographing a site which had been bombed overnight. Iraqi authorities insisted those whom they had detained must leave, – immediately. And so commenced a dangerous journey from Baghdad to Amman. A bomb hit the road along which the CPT convoy was traveling, and a driver lost control of his car. Several CPT members were severely injured in the accident. Cliff Kindy suffered a head wound and was bleeding profusely. Fortunately, several Iraqis who had passed the overturned car risked their lives to help get the passengers to a hospital. Years later, the team members returned to Iraq, seeking to thank all who had helped them survive.

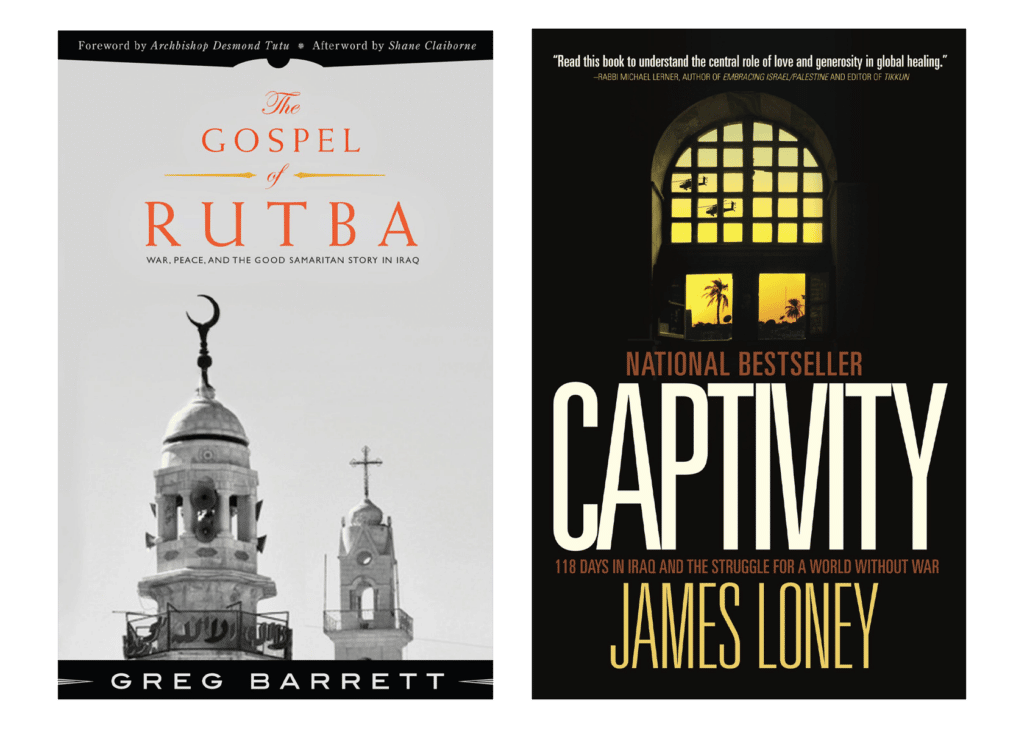

Greg Barrett’s The Gospel According to Rutba narrates this riveting and yet heartening story.

Following the Shock and Awe bombing, several CPT members began to vigil outside of detention centers where Iraqis, rounded up by U.S. military forces, had been imprisoned. Iraqi families often had no idea what their loved ones were charged with or where they were taken. CPT decided to accompany families in their efforts to follow imprisoned Iraqis. Carefully and steadily, team members approached detention sites and built relationships with the U.S. military officials in charge. They interviewed dozens of families, helped develop support networks, and kept track of seventy-two cases of Iraqis detained in U.S. prisons.

Two Palestinian who had been students at an Iraqi University visited our VitW team in Amman, Jordan, shortly before we headed to Iraq in December of 2003. The young men talked about their harrowing six months as prisoners in the U.S. Bucca Compound, south of Basra. They had been arrested as “third country nationals,” TCNs, detained because their ID cards identified them as Palestinians. Perhaps their ability to speak English helped them persuade a three-judge tribunal to release them. Several of their friends still endured deplorable conditions in the makeshift desert prison. The students begged us to visit them. CPTs’ data base identified the officer in charge of the prison and also helped us connect with the brother of one prisoner. With him, we traveled to the Bucca Compound and were able to witness the tearful reunion of the brothers and learn from the visit with all three prisoners about the awful conditions they endured. Later we learned that Ali Baghdadi, the founder of ISIS, had been imprisoned both there and in Abu Ghraib.

CPT, through interviews, was already learning about horrendous conditions inside Abu Ghraib. The team conveyed their concerns to journalist Seymour Hersh, sparking eventual condemnation, worldwide, as the scandal of U.S. human rights abuses inside Abu Ghraib was exposed.

Another imprisonment deeply affected all who were involved with the Christian Peacemaker Teams during the chaos which followed the U.S. invasion and occupation. Four CPT members were taken hostage, in Baghdad, on November 26, 2005. Tom Fox was killed and the remaining three were released, after 118 days, on March 23, 2006. Jim Loney’s gripping memoir of the ordeal, Captivity, is the most challenging reflection on war and peace I’ve ever read. “Whenever we soil someone else with violence,” Jim wrote in a later essay, “whether through a war, poverty, racism or neglect, we invariably soil ourselves. It is only when we turn away from dominating others that we can begin to discover what the Christian scriptures call ‘the glorious freedom of the children of God.’”

The call to truly turn away from dominating others while also struggling to end all wars requires a tremendous reckoning. We must grapple, personally and communally, with dark stains of colonialism, racism, and falsely presumed superiorities. At the same time, we must recognize our fundamental interconnectedness. With profound regard for CPT’s resilience and treasuring the role it will play in the further invention of nonviolence, I’m reminded of Dag Hammarskjold’s words: “For all that has been, thank you. To all that shall be, yes.”

Kathy Kelly co-coordinates the Ban Killer Drones campaign which seeks an international treaty banning weaponized drones. In 1996, she co-founded Voices in the Wilderness which was succeeded by Voices for Creative Nonviolence (2005 – 2020).