By Emily Green

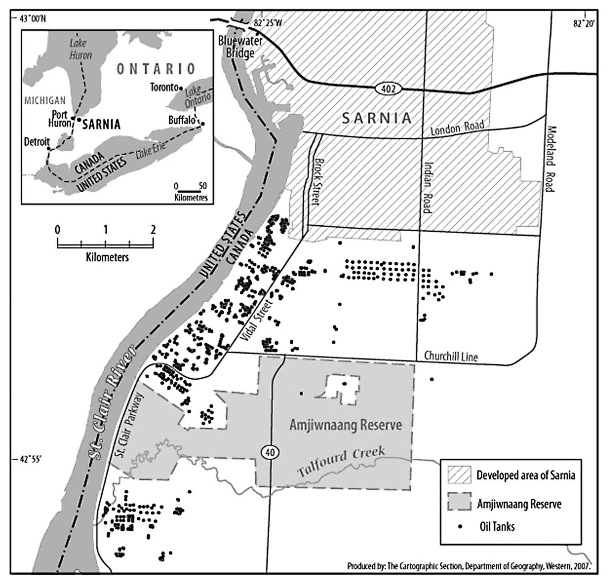

For several years, youth from Aamjiwnaang First Nations reserve have invited allies to visit their community for what they have coined the Toxic Tour. They have created this tour to give participants a glimpse into the realities that they live with every day: their home is surrounded by petroleum and chemical refineries, their air smells like a laboratory experiment, and their health and safety are constantly being put at risk by corporate powers and limited government regulations.

The tour group of about 150 people was greeted with a large feast at the Aamjiwnaang community center that included traditional foods like wild rice and venison stew. We were welcomed by an elder who thanked us for coming to witness their reality; he shared that folks from Aamjiwnaang used to join the tour, but that fewer come these days, because they know the sites of the tour so intimately that it feels redundant.

Members of the Aamjiwnaang community spoke about the constant risk of spills, leaks, and eroded health. The condition of living in relationship with land that is surrounded by 40% of Canada’s oil refineries holds many layers of emotion: fear, anger, lack of control, frustration, and sadness. This tour is one way for the community to be witnessed in their struggles, and for them to gain support. One of the main requests from the tour leaders is for participants to share their story, and to take action when the community calls for action.

One of the most visceral lessons that I took away from my Toxic Tour experience is the connection between pollution and colonialism. As we stood at the site of the Aamjiwnaang band office, which until recently also housed the community’s daycare, I took in the flairs and smokestacks of the chemical refinery across the street. No one should live, work, or watch children to play in proximity to these industries. The racism inherent in the choice to position these refineries on all three sides of an Indigenous reserve does not feel accidental; the lack of governmental systems of accountability to regulate and minimize the harms of these industrial sites feels aligned with other historical and present incidents of environmental racism.

At his year’s Toxic Tour, the community launched an app called “Pollution Reporter” that will help those living in Chemical Valley (the area of Sarnia and Aamjiwnaang) to track incidents of leaks and spills, and the impacts that the industry has on residents’ health. This data collection is one way that Aamjiwnaang residents can hold industry accountable to government regulations, while also showing patterns of illness relative to location.

__________________________

Map retrieved from: Luginaah, Isaac, Kevin Smith, and Ada Lockridge. “Surrounded by Chemical Valley and ‘living in a Bubble’: The Case of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, Ontario.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 53.3 (2010): 353-70. Web. 20 Nov. 2019